Kendrick Lamar

To Pimp A Butterfly

Release Date: Mar 16, 2015

Genre(s): Rap

Record label: Interscope / Aftermath

Music Critic Score

How the Music Critic Score works

Buy To Pimp A Butterfly from Amazon

Album Review: To Pimp A Butterfly by Kendrick Lamar

Fantastic, Based on 34 Critics

Based on rating 10/10

There is a strong sense in which even attempting to write 'a review' of an album like Kendrick Lamar's second album, and masterpiece, To Pimp a Butterfly, is foolhardy. It's one of those pieces of art that comes along something like once a decade, so layered with meaning, so knotted up with intent and resonance, so of-its-time yet treating issues and themes that can span eras, that I am still discovering and uncovering different meanings, references, and picking my way to an imperfect understanding of it, despite having had it - literally - on repeat, daily, since its release last month (was it just last month? It already feels like music I've lived with for years). It's the sort of album that deserves – no, demands – to be really listened to, worked out for oneself, and - in case this is all making it sound like homework or duty, god forbid - relished and delighted in, in all its jazzed up, funked out, soulful, loud, proud, angry, sad and beautiful glory.

Based on rating 10/10

“Your horoscope is a Gemini, two sides/So you better cop everything two times.” In an album boiling over with thesis statements, this one, from the final verse of opening track Wesley’s Theory, is particularly constructive. To Pimp A Butterfly is an album about contradictions—the contradictions of fame and artistry, of escape and home, of Kendrick Lamar himself, and the schizophrenic condition that W.E.B. Du Bois’ termed “double consciousness” in The Souls of Black Folk.

Based on rating 10/10

Head here to submit your own review of this album. Since giving hip-hop its most celebrated album (good kid m.A.A.d city) and verse (on Big Sean's 'Control') of the last five years, Kendrick Lamar has had the eyes of the world on him, wondering where his highly observant mind would go next. When he gave us 'i', a single released last September, it was viewed by many as "safe" or overly earnest, and aiming for mass appeal and broad cultural acceptance.

Based on rating 5/5

As angry as Kanye, as funky as D’Angelo, more self-flagellating than Drake and as righteously cosmic as Erykah Badu, Kendrick Lamar’s latest album does not disappoint. His breakthrough album of 2012 cast this native of Compton, California as a “good kid” from a “maad city”, a poet promoted out of the war zone to tell his tale. Months in the anticipating, its follow-up, To Pimp a Butterfly (the title improves after one play), finds Lamar eyeing up America, turning his back on the lure of easy stardom.

Based on rating 5/5

Judging from the pages upon pages already written about Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly, you might think that critics have already exhausted the conversation within just the first week after its surprise release. Some valuable interpretations have surfaced, and the exuberant praise that some have lavished on the album is due. But so many reviews have heaped up recycled platitudes about the album’s somehow-surprising blackness, its supposedly-inscrutable complexity, and its take on the suddenly-topical string of police murders that have recently gained mainstream awareness (but have been going on for decades) that a complete reading of the album’s lyrical content hasn’t yet breached the press.

Based on rating A+

In piecing together his new album, Kendrick Lamar left certain things behind. The 27-year-old Compton rapper has largely abandoned contemporary hip-hop structures in favor of a cosmic splat of jazz, soul, and funk. He’s said goodbye to his peers in Black Hippy and, with the exception of Snoop Dogg’s Slick Rick impression on “Institutionalized” and Rapsody’s pro-black verse on “Complexion (A Zulu Love)”, the need for guest rappers.

Based on rating 5.0/5

A weird moment occurs at the end of Kendrick Lamar’s sophomore album, To Pimp A Butterfly. Following the conclusion of “Mortal Man,” a spoken word poem that is unveiled piece-meal throughout the album, the TDE-emcee asks Tupac Shakur a question. “How would you say you managed to keep a level of sanity?” Kendrick says. “By my faith in God, by my faith in the game,” Pac replies before continuing, “and by my faith that all good things come to those that stay true…” Clearly it was all a dream, which Kendrick actually referenced in a 2011 interview with Home Grown Radio.

Based on rating 5/5

On his game-changing debut album, Kendrick Lamar wrote vividly about the world he grew up in. On his astonishingly accomplished new album, Lamar writes even more vividly about the world at large. It's in every way an expansion of Lamar's vision, with far more exciting, funky and outgoing music to accompany it. To make a leap of that magnitude cannot be underestimated.

Based on rating 4.7/5

Review Summary: "We ain't even really rappin', we just letting our dead homies tell stories for us." Kendrick Lamar writes his music through colors. “Lamar works synesthetically,” says audio engineer Derek Ali in the Compton-based rapper’s Rolling Stone feature out this month. According to Ali, Lamar demanded certain colors be created within the songs on To Pimp A Butterfly.

Based on rating 9.3/10

Kendrick Lamar’s major-label albums play out like Spike Lee films in miniature. In both artists’ worlds, the stakes are unbearably high, the characters’ motives are unclear, and morality is knotty, but there is a central force you can feel steering every moment. The "Good and Bad Hair" musical routine from Lee’s 1988 feature School Daze depicted black women grappling with colorism and exclusionary standards of American beauty.

Based on rating 4.5/5

Could you kill the person sitting next to you? Physically, mentally, spiritually: Could you go through with it? And then, could you live with yourself? I am safe and fortunate enough to have never truly, dreadfully contemplated such a question as an immediately practical concern; and so, I imagine, are most of our readers. I wish I could say the same for Kendrick Lamar, who, in his music, often wrestles with death and destrudo as if his studio were the dreadful belly of a ghost that has him trapped. Kendrick Lamar has witnessed death, he has suffered its proximate consequences, and he has lived to resent its power over him and the ones he loves.

Based on rating 9/10

Kendrick Lamar :: To Pimp a ButterflyTDE/Aftermath/Interscope RecordsAuthor: Jesal 'Jay Soul' PadaniaI realized something this morning when looking in the mirror, bleary-eyed: I'm not black! After listening to D'Angelo's "Black Messiah" I somewhat suspected it, but the biggest hypocrite of 2015's "To Pimp a Butterfly" confirmed it. Other surprises: not from Compton, never met a Blood or a Crip, liked Rae Sremmurd's "Unlock the Swag" (actually so did Kendrick Lamar)... Rest assured - his new album is full of far more meaningful revelations, and even if I'm not the intended audience, I get it.

Based on rating 9/10

Kendrick Lamar is not reluctant when it comes to being the voice of a generation. He may sound conflicted about his actions on record—insecure, remorseful, angry, pensive, probing—but he doesn't shirk the responsibility that comes with the power he has over his listeners. That's an important idea to understand when unpacking the dense opus that is To Pimp a Butterfly, Lamar's insanely anticipated third album that unexpectedly dropped in the evening the Sunday before last.

Based on rating 4.5

Kendrick Lamar’s extraordinary To Pimp A Butterfly shares a good deal of common ground with D’Angelo’s recent Black Messiah, not simply in its rush-release mechanism (available to download suddenly, ahead of a planned release date) but also in its excoriating examination of contemporary race issues in the US. Both albums seem to capture a rage and desire to examine in the wake of Ferguson, as well as featuring bold investigations of their creators’ internal vulnerabilities behind the external egos. Both albums have been hailed instantly as important works, although both ought to resist snap judgements.

Based on rating 9/10

"Mom, I'm finna use the van real quick. Be back in 15 minutes"Familiar to anyone who had Kendrick Lamar's now seminal 2012 album good kid, m.A.A.d city in heavy rotation, these words are uttered by Lamar after "Compton," before slamming the door on the modest 1996 Chrysler Town and Country family minivan featured on the album's weathered Polaroid cover, theoretically denoting the official end of the album. On the deluxe version though, a couple of seconds elapse before the sound of a supersonic jet taking off signals the cue to luxuriously partake in the 3Ws, (women, weed and weather) — a stark contrast to the always-on survival mode of the rest of GKMC — via the Dr.

Based on rating 4.5/5

In the thick of its release, the conversation surrounding Kendrick Lamar's extraordinary new album is bound to be mired in debate about its proximity to, or more specifically the distance it keeps from, the rap genre. Which is to say, To Pimp a Butterfly will inevitably be held up against Lamar's 2012 breakthrough, Good Kid, M.A.A.D City, judged against that album's status as a young classic of the hip-hop genre and the reputation the rapper built in its wake. Lamar earned that reputation by being an artist with that rarest of skill sets: technical mastery, narrative focus, and social consciousness, able to conjure up comparisons to 2Pac, Biggie, and Illmatic-era Nas.

Based on rating 9/10

In the run-up to the release of To Pimp a Butterfly, Kendrick Lamar seemed different. Maybe he grew timid of the spotlight he so suddenly commanded since a few years ago, or maybe the controversial response to the album’s early singles—criticism that he was selling out, or that he was blaming the black community for their own disadvantages—was getting to him, but the consensus was that he appeared conflicted. In the press, during performances and on interview circuit, it was like we were witnessing a changed man.

Based on rating 4/5

In the days since Kendrick Lamar’s third album was released online – so unexpectedly that it appeared to take even his record label by surprise – its creator has been mentioned in the same breath as some very lofty names indeed. Reviewers have invoked Parliament-Funkadelic and Sly and the Family Stone. In one New York Times profile alone, the 27-year old rapper was variously likened to Curtis Mayfield, Marvin Gaye and – wait for it – Mahatma Gandhi, the latter a comparison that even the most vociferous fan of Lamar’s 2012 breakthrough album Good Kid MAAD City might think amounts to gilding the lily.

Based on rating 4/5

As an example of music providing a city’s A-Z, few could match Kendrick Lamar’s 2012 homage to Compton, ‘Good Kid, m.A.A.d city’. Three years on, ‘To Pimp A Butterfly’ has been mooted as a record that would speak openly about social injustice, speaking for a whole country rather than personal experiences closer to home. The influence of a new producer hits with the opening flurry of ‘Wesley’s Theory’, Kendrick’s dense odyssey coming into its own once it begins to settle.

Based on rating 4/5

Kendrick Lamar might be the new king of west coast hip-hop, but don’t think it’s a crown he’s wearing lightly. Exploring the dangers of being a thoughtful youth forced to come up hard on the streets of Los Angeles’ gangster-rap capital, the Compton MC’s 2012 major label debut, ‘good kid, mAAd city’, told the story of a young man at war with himself, in a community at war with itself. Fast-forward to the present, and that war has become endemic, the lie of a ‘post-racial society’ peddled in the wake of Obama’s first presidential win brutally exposed by the acquittal of 17-year-old Florida teenager Trayvon Martin’s killer, and nationwide unrest following police killings of African-American men in Ferguson and New York.

Based on rating 4/5

Hashtag this one Portrait of the Artist as a Manchild in the Land of Broken Promises. Thanks to D'Angelo's Black Messiah and Kendrick Lamar's To Pimp a Butterfly, 2015 will be remembered as the year radical Black politics and for-real Black music resurged in tandem to converge on the nation's pop mainstream. Malcolm X said our African ancestors didn't land on Plymouth Rock, Plymouth Rock landed on us.

Opinion: Fantastic

So soon after it was unexpectedly issued late Sunday, "To Pimp a Butterfly," the new record by Compton-raised rapper and lyricist Kendrick Lamar, is still settling in, less a voluminous whole than a germinal swirl of phrases, grooves, bass lines and themes both personal and political working to find purchase. "I got a bone to pick!" "I went to war last night. " The bounced-beat chants of "King Kunta!" "Obama say what it do?" The dance hall hook in "The Blacker the Berry"; the revelatory last verse of "For Free.

Opinion: Excellent

Calling mainstream hip-hop a series of compromises is unfair, but the genre is far from where it was even a decade ago. It’s still a privileged space for black expression, but has also become extremely conscious of everyone else listening in. Broadly speaking, it has reframed its concerns as universal, not specific. It is, by and large, polite — a warm and welcoming host.

Opinion: Absolutly essential

Kendrick Lamar To Pimp a Butterfly (Interscope) A sampled vocal of Jamaican crooner Boris Gardiner poses a question as explicit and prescient now as when asked in 1974: "Who will deny that you and I and every nigger is a star?" Trekking barbwire thickets of the dense, pitfall-enriched forest called "existence of (successful) black men," Kendrick Lamar machetes strange new arteries into the heart of the concrete jungle. Rejecting all actions from his debut, one of the great bows in any genre – 2012's good kid, m. A.

Opinion: Absolutly essential

To Pimp a Butterfly is not a rap album. Rather, it is a funk manifesto, a screed that grooves in the same grooves that Sly and the Family Stone sparked on There’s a Riot Goin’ On (1971) and Mayfield on Curtis (1970); it carries those grooves forward like torches into the post-millennial dusk. Rather, it is a packed, self-reflexive novel of a thesis statement, Kendrick Lamar proclaiming himself here a “literate writer,” this his sprawling opus that even rocks annotation (the echoing, hollowed-out footnote of “These Walls” unravels with Kendrick remarking after a pointed bar that “that sentence so important” and referencing us back to his first verse so that we can dig there is no metaphor present on To Pimp a Butterfly without at least two meanings).

Opinion: Absolutly essential

From the dusty sample that kicks off To Pimp A Butterfly — the hook from Boris Gardiner’s blaxploitation ballad ‘Every Nigger is a Star’ — Kendrick Lamar makes his intentions clear: this will not be a polite album, a comfortable ride, the soundtrack for a party. And why would it be? The last several years have been a reminder of America’s Big Lie: that a country built on the backs of slaves still hasn’t delivered on the promise of all men being created equal, not when cops and assorted vigilantes can murder black people without repercussion. Where Lamar’s good kid, m.A.A.d city told the story of one man (a boy, really), To Pimp A Butterfly tells the story of a nation and a people, through the eyes of that same man.

Opinion: Absolutly essential

opinion byZACHARY BERNSTEIN < @znbernstein > On the night of January 26, 2014, for thankfully only a brief five minutes, Kendrick Lamar was deeply uncool. Capitalizing on the critical adoration and legitimate street credibility of Lamar’s instant classic debut Good Kid, M.A.A.D. City, the Grammys inexplicably paired the upstart rapper for a live performance with Imagine Dragons, a band that represents everything inoffensive and unforgivably dull about contemporary rock music.

Opinion: Absolutly essential

"Remember the first time you came out to the house? / You said you wanted a spot like mine / But remember, anybody can get it / The hard part is keeping it, motherfucker," Dr. Dre says on Wesley's Theory, the funk-indebted opening cut on Kendrick Lamar's perfect follow-up to Good Kid, M.A.A.D City. On To Pimp A Butterfly, he meets that challenge - ramping up his musicality with elements of funk, doo-wop, jazz and spoken-word poetry, debuting a dizzying number of new cadences and diving deeper into the ever-evolving question of what it means to be black in America and the social issues that have lassoed his hometown of Compton in a painful cycle of poverty.

Opinion: Absolutly essential

So what would the late Tupac Shakur and the very much living Kendrick Lamar talk about if they were ever to meet face to face in the next life? According to Lamar, they'd dish on economic inequality, revolution and racial metaphors about caterpillars and butterflies. The imaginary conversation, audacious in the way it digitally melds two of hip-hop's leading voices from different eras, takes place during the 12-minute “Mortal Man,” as much philosophy treatise as song, and one of several flights into the surreal on Lamar’s second album, ”To Pimp a Butterfly” (Top Dawg/Aftermath/Interscope). This is a modal window.

Opinion: Fantastic

No accomplishment in hip-hop is rarer or more celebrated than the classic debut, so the rap world was eager to welcome Kendrick Lamar’s breakthrough Good Kid, M.A.A.D. City as one in 2012. Never mind that it wasn’t actually Lamar’s first album: Good Kid announced the arrival of a major talent, and like every mythologized rap debut, it seemed almost presciently aware of its own importance.

Opinion: Fantastic

Becoming an adult ultimately means accepting one's imperfections, unimportance, and mortality, but that doesn't mean we stop striving for the ideal, a search that's so at the center of our very being that our greatest works of art celebrate it, and often amplify it. Anguish and despair rightfully earn more Grammys, Emmys, Tonys, and Pulitzer Prizes than sweetness and light ever do, but West Coast rapper Kendrick Lamar is already on elevated masterwork number two, so expect his version of the sobering truth to sound like a party at points. He's aware, as Bilal sings here, that "Shit don't change 'til you get up and wash your ass," and don't it feel good? The sentiment is universal, but the viewpoint on his second LP is inner-city and African-American, as radio regulars like the Isley Brothers (sampled to perfection during the key track "I"), George Clinton (who helps make "Wesley's Theory" a cross between "Atomic Dog" and Dante's Inferno), and Dr.

Opinion: Fantastic

If there was an apex of the blaxploitation era, it came in 1974. It was three years after “Shaft” made a crater in pop culture, and the floodgates opened wide for the genre. Timeless sex symbol Pam Grier wore a miniskirt and wielded a shotgun as Foxy Brown, Football immortal Jim Brown karate-kicked crooked cops. Marki Bey unleashed a pack of black zombies on the white mobsters that murdered her lover.

Opinion: Fantastic

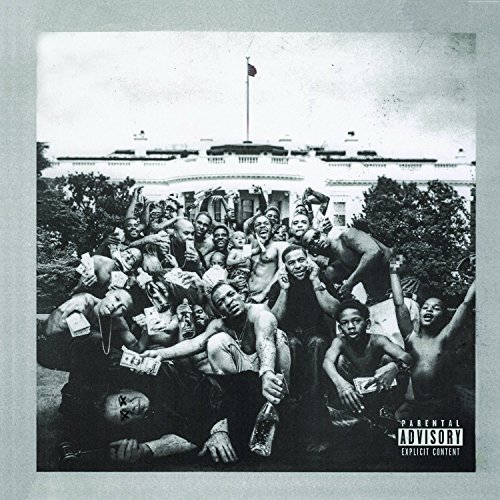

When Kendrick Lamar's formidable single 'The Blacker The Berry' dropped last month, it blew all fears of a radio-friendly album out of the water, presenting the flip side of 'i's evangelical self-love and foreshadowing a release boiling over with racial and political tension. The subsequent unveiling of the cover art made Lamar's mission statement clear; his gaze had turned from the troubled streets of his native Compton to America at large. Where good kid m.A.A.d city followed a reasonably linear autobiographical narrative, To Pimp A Butterfly erupts into a thousand different strands at once, forming an unwieldy, gargantuan collage of conversations that would be a disaster in less capable hands.

Opinion: Fantastic

I’ve not been entirely kind to Kendrick Lamar lately. After the release of the lead single “i”, a blithely upbeat guitar-based track with the repeated hook “I love myself”, I predicted that ‘Kendrick’s next album is gonna be the rap equivalent of a book with purple swirls and Buddhas on the cover called ‘Releasing The Inner YOU’’ and that it would end with ‘an extended coda featuring Jaden Smith talking about vegetables’. In the end I wasn’t entirely wrong about the coda – except it’s a conversation between Kendrick and 2Pac, built from old interview footage, and it’s human flesh being eaten, not vegetables.

'To Pimp A Butterfly'

is available now